Restoring a 1971 vintage Teac A-4070 tape deck

2023

On the NextDoor social network, I found a post by Stephen Atkins looking for a nearby tape deck technician. There was a special meaning behind his request: Steve’s father, being blind, had preserved his memoirs and family events on reel-to-reel audio tape, not in photographs. When Steve’s Dad passed away 30 years ago, his recorder and tapes became lost in storage until recently.

From his online bio, I realized Steve himself was quite an expert with a long career in audio production. Still, he wisely decided not to just plug in the recorder, but to seek help. My own experience — side jobs during the ’60s in high school and college, at radio stations and a recording studio — was antiquated but relevant. With both the tape deck and me being relics from the same era, I thought we might be compatible.

The photo above shows the deck as it appeared when Steve brought it over, after 30 years of storage in its original shipping carton. The tape head cover had fallen off and its internal shield had come unglued, but otherwise things looked OK until I removed the case and began moving the mechanical parts by hand. The reel brakes were extremely tight and squeaky, the tape tension arms were frozen, the level controls were nearly impossible to rotate, and some pushbutton switches were stuck. Inside, the drive belt had stretched with age and fallen completely off its pulleys.

Was I up for performing an operation on Steve’s prized, sentimental possession? I wasn’t quite sure until I found a scanned service manual for a later, but similar, model online. Having a schematic and assembly drawing, now I could understand the anatomy before undertaking surgery, so with the informed consent of the patient (actually the patient’s guardian) I went ahead.

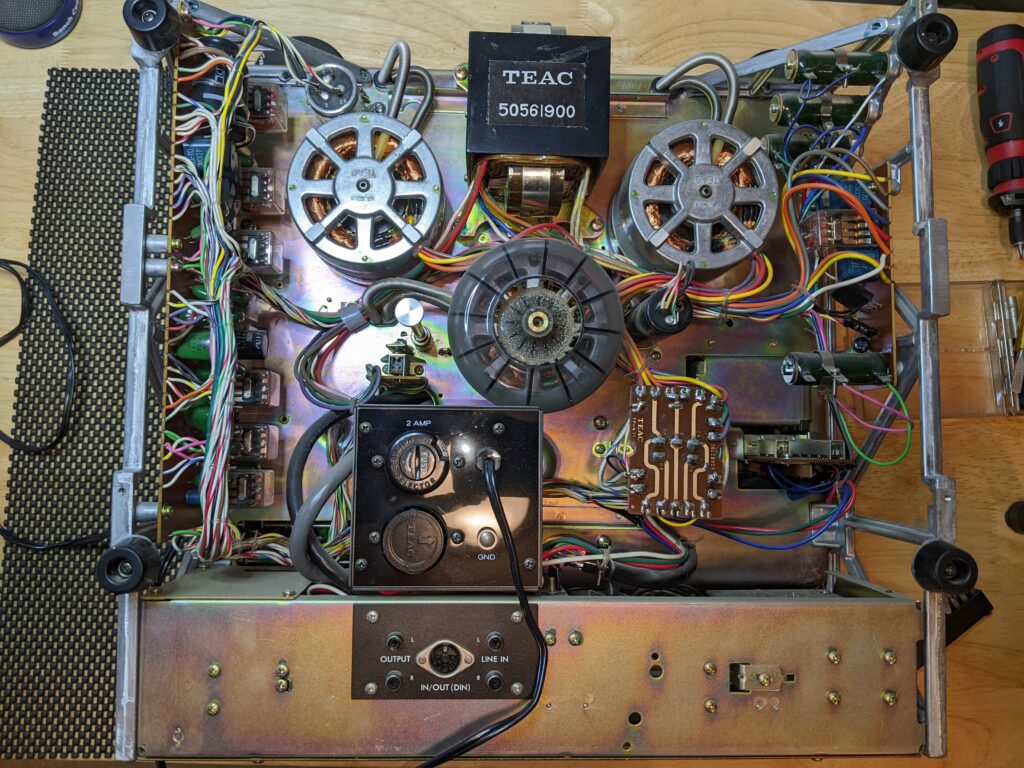

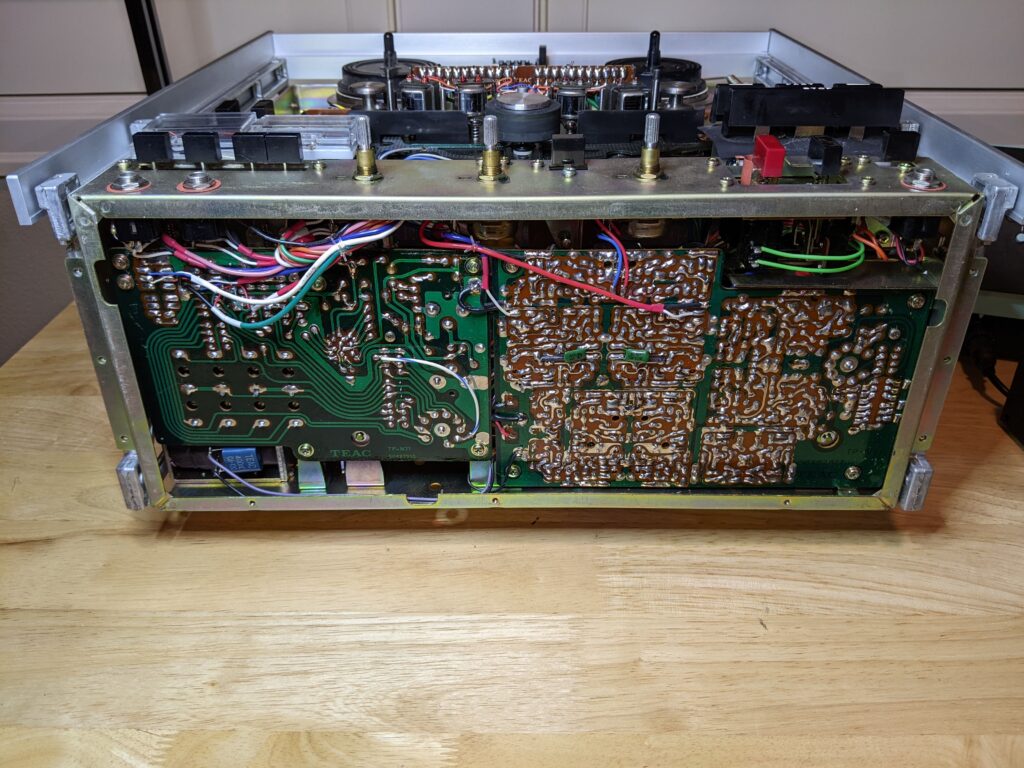

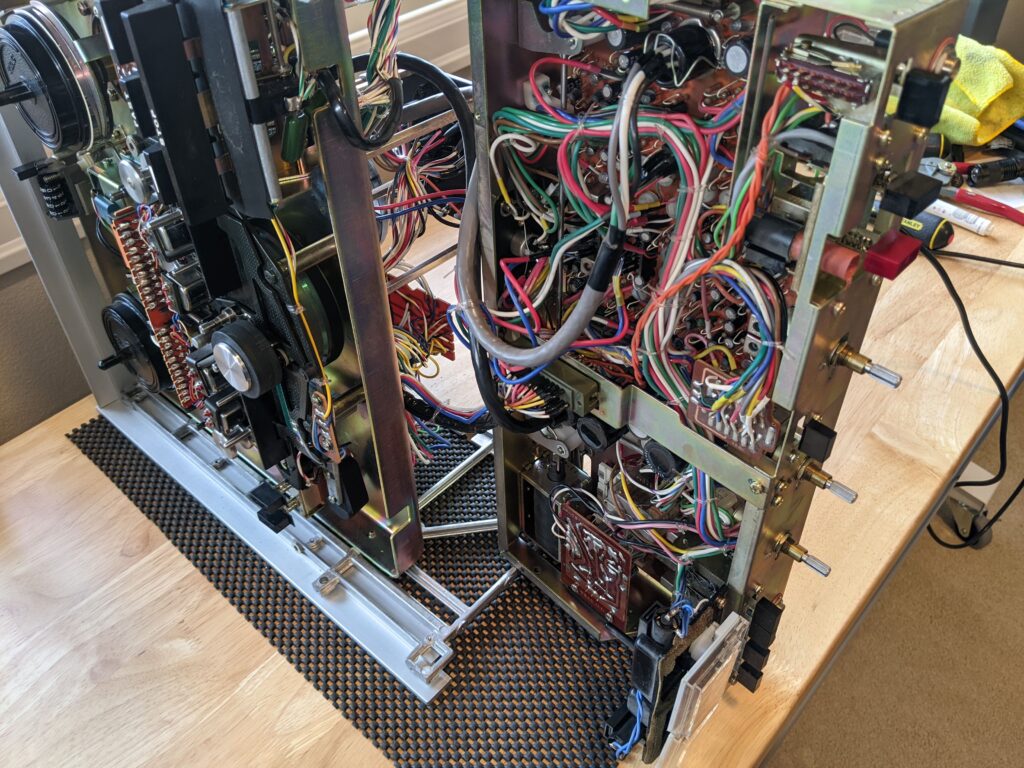

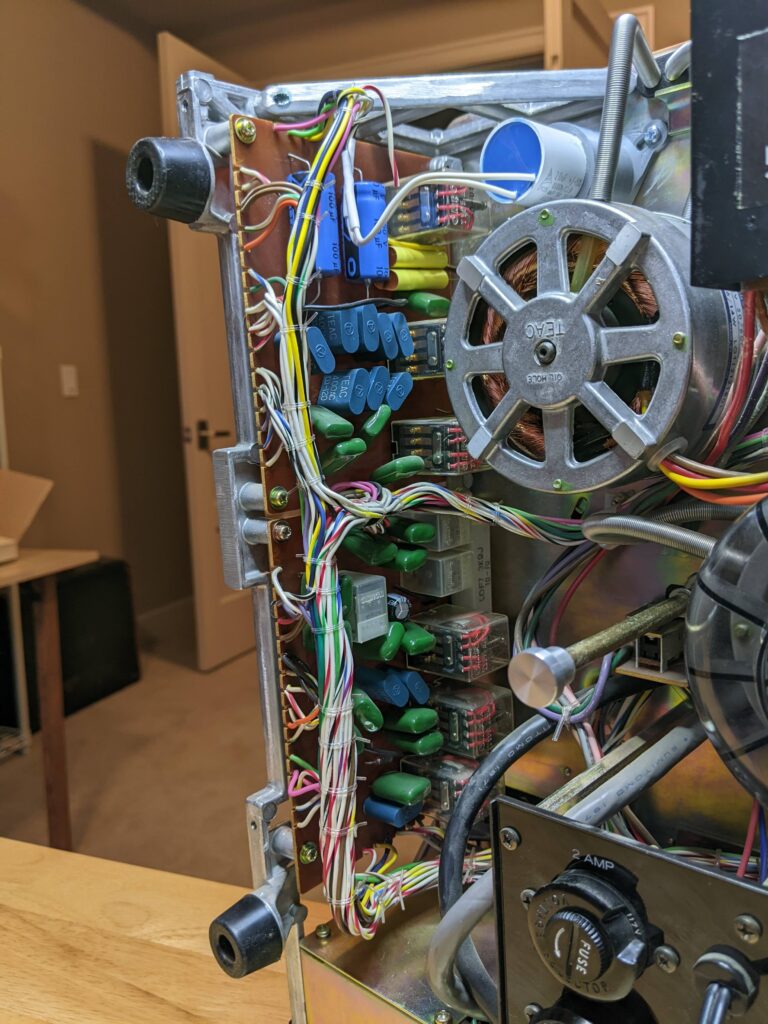

The solid construction of the deck was reassuring. Weighing 50 pounds, it had a thick steel chassis, a cast aluminum frame, three big motors, a power transformer, and half a dozen printed circuit boards bristling with relays and solenoids. I opted not to power up the deck — which could damage irreplaceable components if there were short circuits — and to tackle the purely mechanical issues first.

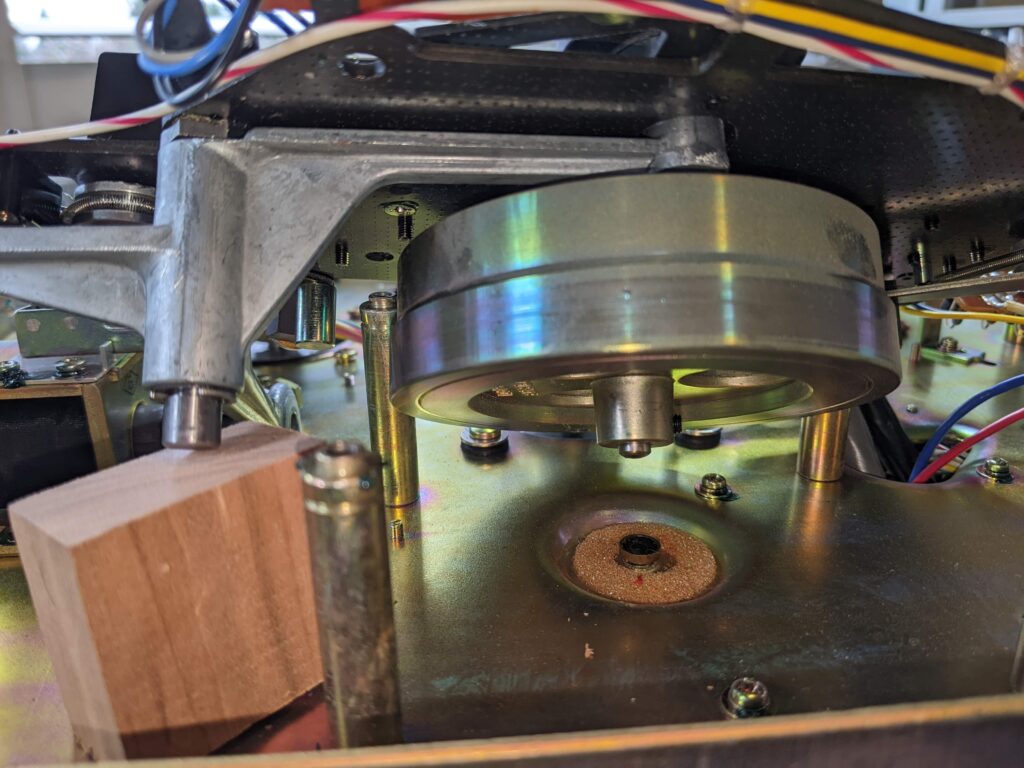

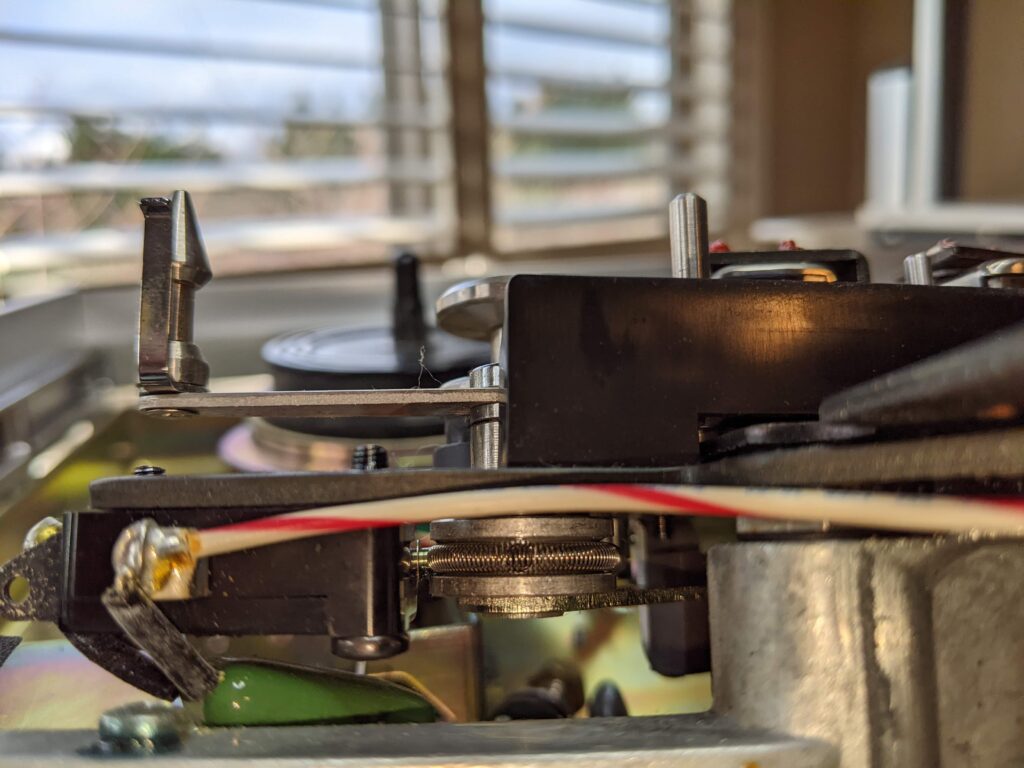

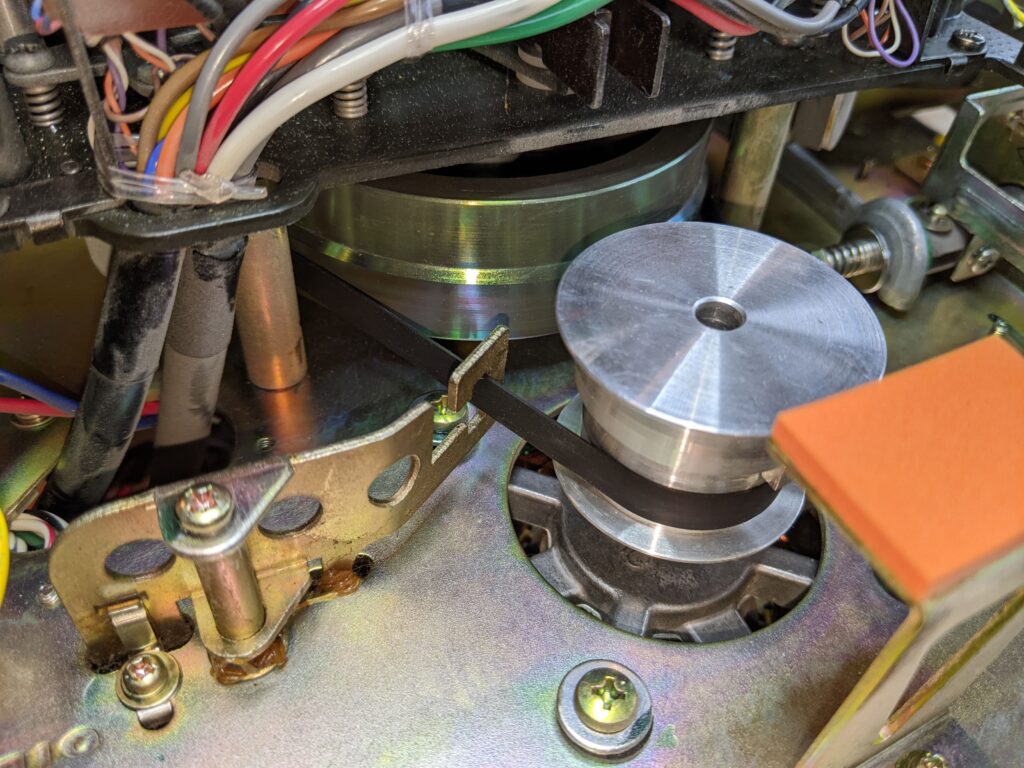

The four tape heads and capstan/flywheel were supported by a thick steel plate. Since I didn’t want to unsolder the connections to the heads, I just detached the plate from the chassis and tilted it up, supported in on a wood block. That allowed enough access to disassemble and lubricate the tape tension arms, lubricate the capstan bearing, and mount the new drive belt. So far so good.

The electronic components most affected by aging — even worse when sitting unused — are electrolytic capacitors. Some restorers replace them all preemptively, while others just cross their fingers and turn on the power. Faced with more than 60 of them, I decided to start by replacing the two dozen most vulnerable ones — power supply filtering and motor capacitors — that could damage other parts if they failed.

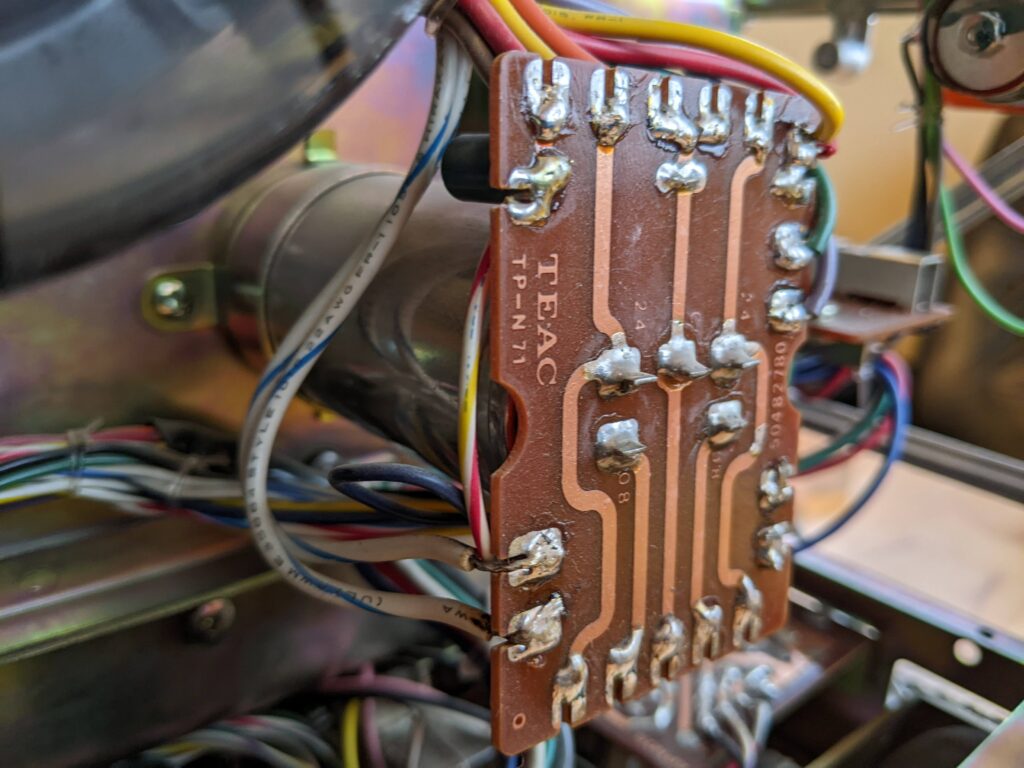

The reel motor capacitor had 4 elements, housed in a can with its 5 tabs soldered to a PCB, and I was nervous about heating all those tabs at once while pulling the capacitor off. But fate smiled! Despite the otherwise stellar quality of the deck, the factory had failed to seat the capacitor fully onto the board. I was able to get needle nose pliers and diagonal cutters in to snip some of the tabs loose before desoldering.

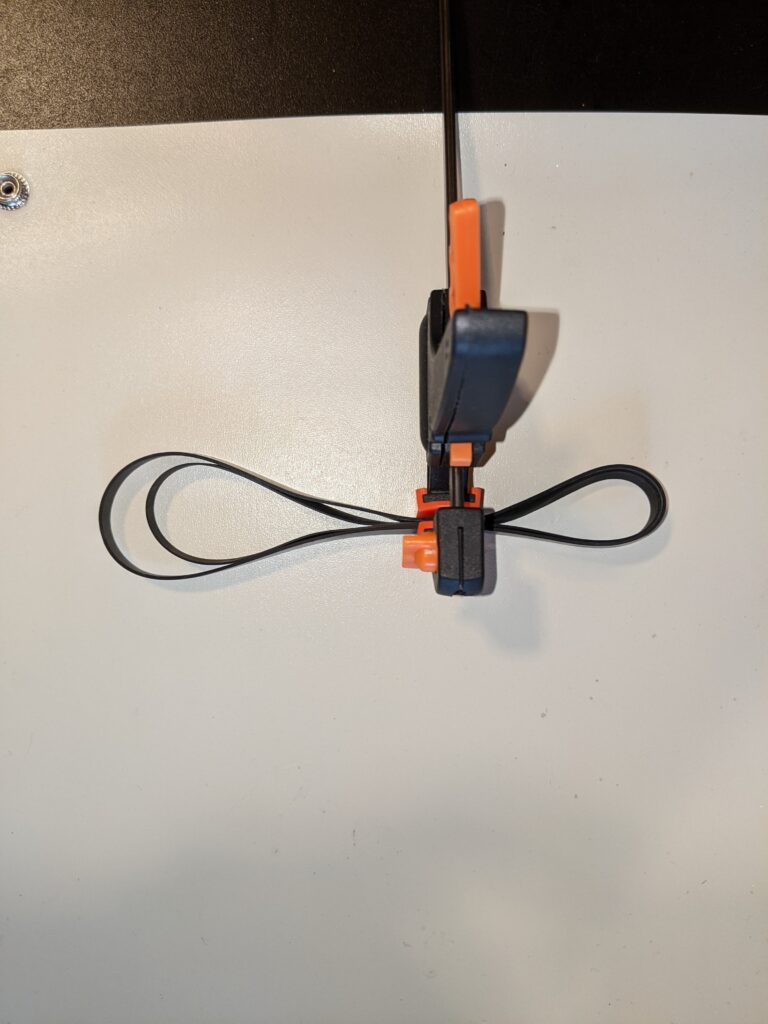

The three capacitors housed in chassis-mounted cans were replaced with modern, smaller cylindrical capacitors. So I had some fun designing and 3-D printing plastic mounting brackets to adapt them to the original chassis mounting holes.

The remaining electrolytic capacitors were just a matter of patiently desoldering and replacing them on their respective printed circuit boards. I appreciated that the deck was obviously designed for repairability — by turning it to various positions, I could reach the bottom and top of most of the boards. Before reassembling, I cleaned all of the switches and level controls with spray-in contact cleaner, then re-lubed them until everything worked smoothly.

It was time for the Moment of Truth: power up — cautiously. A Variac was used, gradually increasing the line voltage while watching for any signs of overheating or smoke. Everything looked good, so it was time for mechanical and electrical alignment.

Mechanical alignment consisted of checking and adjusting the torque from the reel motors and brakes. The reel brakes were very tight and squeaky, even adjusted to their loosest setting. I solved this by “exercising” the brake springs, which had apparently stiffened in their old age (like people do). The motor torques were measured using spring scales, pulling on a string wrapped around the hub of a tape reel. Luckily, I was able to get everything within factory specs, and the deck demonstrated its rewinding, fast forwarding, reversing, and stopping prowess without snapping or spilling any tape.

Before performing electronic alignment, I cleaned and demagnetized the heads and guides. An oscilloscope was connected to the outputs, and a signal generator fed to the inputs.

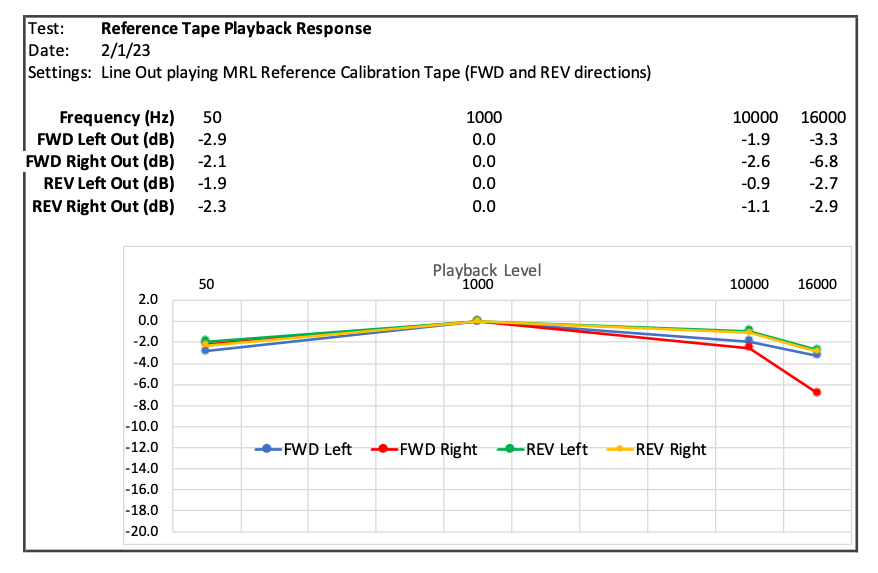

A reference calibration tape was mounted, and the playback levels of prerecorded test tones on the tape were measured on the scope. Only minor adjustments had to be made to the playback head azimuth to peak the high-frequency response, and to bring left and right channels into phase match. A response plot showed the deck was achieving close to factory spec.

Since the primary intended use of the deck was to play back Steve’s archival tapes, didn’t attempt a full alignment for recording, but confirmed that recording does work.